If someone ever asked me what surprised me about living in Africa, I’d have a million answers. Nearly every day held in its ebony hands something to learn or figure out or shake my head over: a motorcycle carrying a coffin. A girl made to sell banana pancakes for a dime in a dangerous neighborhood rather than go to school. Birds the color of the sky.

But I could never have known how working and living among and helping the powerless would change me–to the point it’s now a vital spiritual discipline in my book–and quite arguably, in God’s.

Even now, years later, I’m pawing around in my mind to tell you how, exactly, or what left me a different person.

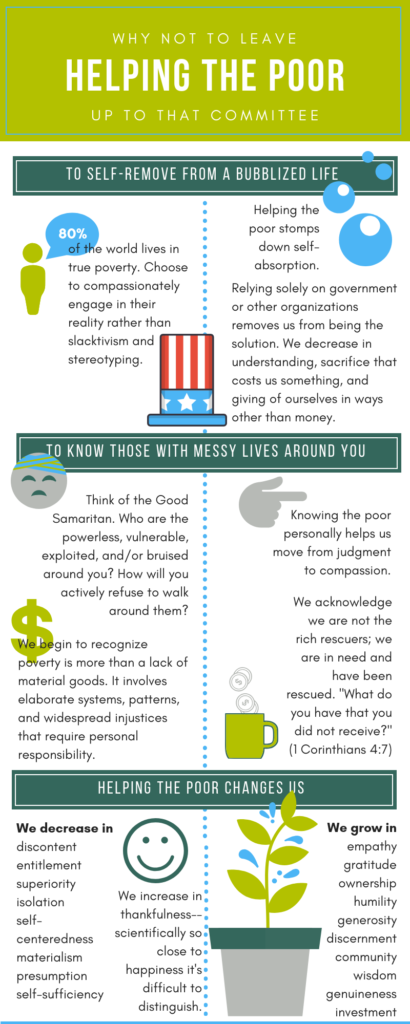

Some of them, you can glimpse in the graphic on my right.

But some of them, I see in an ancient story.

Helping the powerless: That time it saved his family

There’s this narrative tucked in 1 Samuel 30 that just never makes the children’s Bibles. Maybe that’s because a foreign army burns the Israelite city of Ziklag to the ground, then abducts all of King David’s wife and kids, plus the families of his men.

Not exactly “Sleep tight, sweetheart!” material.

David and his men are crushed. No doubt they’re fearing the gruesome worst in these pre-Geneva-convention days. The Old Testament reveals that David and the people “raised their voices and wept until they had no more strength to weep” (v. 4). David’s freaking out (“greatly distressed”) that the people might stone him because they were “bitter in soul.”

But though his wife Abigail was taken, he’s learned something from her. He doesn’t seek revenge–as he had planned to do with her first husband, Nabal (25:32-33)–without seeking God first. (This whole chapter is a shining example of David’s leadership.)

This next part may have fallen to a historical footnote under different circumstances: David and his people find an Egyptian in the open country, who they feed and give water to, and “his spirit revived.” They’re all grieving, but somehow they’re still helping the powerless.

And as his story tumbles out, the guy reveals his master, an Amalekite, left him because he was sick. The Amalekites had made a raid, burning Ziklag, see, so the Egyptian was dead weight. Or maybe just virtually dead.

The Egyptian agrees to take David’s men to the Amalekites–who are partying over their victory–as long as they won’t kill him or hand him over.

The cost-benefit ratio of helping the powerless

I’d returned to this story this morning after camping out in Isaiah 58, another chapter worth reading in its entirety. (They pretty much all are.)

I was trying to understand why God likened lifting oppression and injustice–what he calls a “true fast” to the reward of a person themselves being restored. This chapter is packed with over-the-top promises for people choosing to

loose the bonds of wickedness, to undo the straps of the yoke,

to let the oppressed go free,

and to break every yoke?

Is (true fasting) not to share your bread with the hungry

and bring the homeless poor into your house;

when you see the naked, to cover him,

and not to hide yourself from your own flesh?

Again, I see God likening this to spiritual disciplines of worship/holding Sabbath (v. 13) and fasting, or going without in order to draw closer to God. (I’m starting to see the connections between correcting injustice and fasting. Check out Ethical Clothing for Your Family: 4 (Easy-ish) Steps).

Interestingly, the promises in return for lifting oppression have to deal with healing (“your healing shall spring up speedily”) and restoration: “your ancient ruins shall be rebuilt; you shall raise up the foundations of many generations;

you shall be called the repairer of the breach, the restorer of streets to dwell in” (v. 12).

Before you think you’re saving the day–

Here’s the connection, I think.

I once heard David Platt assert something key for me as a helper, and as someone who works with the powerless. He said we are not the rescuers, but the rescued.

In every powerless person, we could see ourselves.

(To be clear, every powerless person is certainly not the poor. And in some cases, the poor are not powerless. Who do you know around you that’s lacking? That in some staggering ways, is powerless?

I’m talking that person divulging their abuse, or the situation in their marriage. That cashier who feels ostracized by her race, or that teacher no one can stand.)

Without Jesus, we are the naked. The homeless. The hungry. The slave.

In fact, God actually requires we become like the poor. Helping the poor acknowledges it’s us who are impoverished, who come empty-handed, with nothing to offer.

God takes us in and delivers us–like the Exodus, like the Cross. But we fail to do the same to others, to clothe and house and feed and see and soothe. We oppress, dishonor our worship, forget the Sabbath he bought, and do injustice.

This, I think, is the brokenness that needs healing; the breach that causes everything to need healing.

Matthew 22 says the second commandment, to love our neighbor–made in God’s image–is like the first, loving God with all of ourselves (vv. 37-39).

When we lift others’ impossible burdens, God heals us–supernaturally, I think, but also through the action itself. We are replaying the gospel over and over as we look in someone else’s eyes.

What was saved

David and his men trounce the Amalekites. And it’s all possible because David seeks God and helps a foreigner who otherwise would have died.

Even in the middle of David’s own intense distress.

And this is the line I love from David’s story, following David’s conquering: “Nothing was missing, whether small or great, sons or daughters, spoil or anything that had been taken. David brought back all” (v. 19).

What seemed like loss was redeemed, and then some.

Because he also took the Amalekites’ herds as spoils–and gave them to all the people who helped him and protected him from Saul when he couldn’t pay them back.

No doubt about it: This speaks loudly to me as a person looking around the last few years and seeing loss. You could say it’s as if things were burned to the ground, and people I love carried off.

(Any chance your family’s in a season like this?)

I love that through David’s own heart of compassion, amidst his own exhaustion and fear, God saves his family and the families around him. The way he’s led his men–to take someone in, even when they’ve been gutted themselves–ends up as God’s vehicle to rescue them back.

I hear echoes of this story centuries later, as Jesus tells the parable of a very good Samaritan.

No, I don’t think we can view helping the powerless as God’s cosmic vending machine. My son needs a 12-step program. Sign me up at the soup kitchen!

But I’ve gotta admit: God’s not bashful about his desire to change and reward us as we step into His heart. For David, it saved his family.

Consider asking God who he’s put in your path, not unlike the Good Samaritan–and how he longs for you to follow him there, helping the powerless.

Like this post? You might like

For the Days When Helping Hurts [You], Parts I and II

31 Things to Be Thankful for Today If You Live in the Developed World

Ways to Help your Giving Keep from Hurting the Poor, Part I

Why We Can’t Afford to Leave Helping the Poor Up to That Committee [FREE INFOGRAPHIC]