My daughter was 14 months old when she got glasses and began to wear the felt purple eye patch I’d stitched for her. Coincidentally, it was the same month, she started walking at last and pushed through her first tooth. We’d noticed she frequently went cross-eyed.

It wasn’t until she could talk that the opthalmologist was able to understand she didn’t have a muscle problem. She had a genetic condition from my side called Dewayne’s Syndrome, from a missing cranial nerve.

It’s one of my earliest memories of grief as a parent.

I felt what seemed a silly, petty sense of loss, considering what so many others endure with their kids. But somehow I felt gut-punched. I wanted so many good things for her.

When do you first remember knowing grief as a parent?

I mean that. When did you first sense that your child carried the potential for your own grief?

Before my daughter got glasses, I recall the loss surrounding the birth of my oldest son.

At seven months along, I was laid off–subtracting our insurance, two-thirds of our income, and so much of my identity and sense of security. I gratefully accepted a crib set someone purchased on clearance, setting aside my vision of a classy nursery.

A car accident at 37 weeks put me in the hospital. We owed $500 on taxes, my computer crashed, and my son’s birth went wildly awry–but safely, thanks to God.

My idyllic version of motherhood evaporated before he left my body.

But my son struggled to nurse for the entire first month, and seemed inconsolable for the first nine months. (I kept searching for teeth and re-Googling colic.) He didn’t sleep through the night till after a year.

His face was cherubic. His demeanor leaned toward the opposite.

Read WHEN YOUR CHILD IS DIFFERENT THAN YOU EXPECTEDGrief, continued

Of course I’ve experienced the full spectrum of emotion as he’s grown, and y’know? I decided to keep the kid.

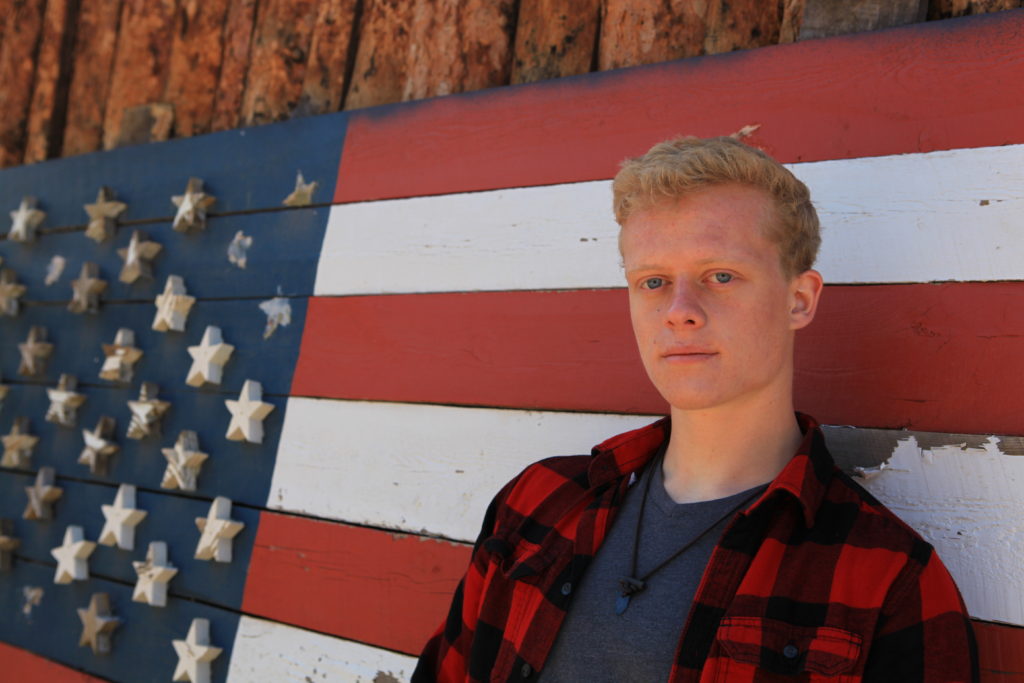

As you read couple of weeks ago would happen, I hugged the waist of my son goodbye this week, cheering him on to boot camp.

Those sculpted pre-military abs beneath his shirt felt so different from the breakable body I tucked into mine after he was born. Or his soft toddler arms with the dimpled elbows.

It still feels weird that he’s taller than me, when he used to fit behind my belly button. (Now his Adidas wouldn’t fit if they tried.)

People have asked how I’m doing with this. And I wish I had a better answer.

He’s on my mind a lot, particularly each morning when I move the magnet on our fridge to the next day of the boot camp schedule.

I’m realizing I experienced more outright grief when he initially signed up. I was just realizing what he, what we all, were committing to—holidays and family time governed by military leave; a delay in his (now paid-for) college education; the culture and danger of military life.

But he’s been leaning toward this for so long. How can I not feel thrilled for him?

My husband came in grinning on Monday night after the call we’d been expecting: My son shouting into the phone a script declaring his safe arrival to the recruitment depot San Diego.

“I’m so proud of him,” my husband—not a gratuitous smiler—said over and over.

So I pray for him throughout the days, like I did this morning when letting the new puppy out at an unholy hour this morning, the sky melting from black to gray.

I thought I might be the parent in tears. Grief assumes so many avatars.

But—perhaps since we’ve had so much stress with our teens in the last year—it feels like another emotionally lade event in the midst of a year of them. So I don’t know if I am numb, or just adding another fierce emotion to my daily slow drip.

He’s reaching for a dream, so that draws away the sting.

Riding the J-Curve

I’ve been marinating on Paul Miller’s concept lately of the J-curve, a pattern of God’s which Miller’s identified in all of Scripture.

“The J-Curve describes the pattern of Jesus’s dying and rising.

“Like the letter J, Jesus’s life descends through his incarnation and then death, and then upward into his resurrection and exaltation. All of the apostle Paul’s descriptions of the gospel in some way trace the pattern of Jesus’s dying and rising. (Rom. 1:3–4, 1 Cor. 15:3–8, 2 Tim. 2:8, Gal. 1:3–4).

“The J-Curve is the map of the Christian life.

“…we should expect a life of dying and rising, that continually re-enacts Jesus’s life.”

I possess an adult choice (not a martyrish one) to descend into death for the people I love, so they can live. My grief as a parent, as a human, is a chance to willfully join Jesus in what it’s like to love humans.

(Jesus said no one takes his life from him, as shown by him walking through crowds who wished to stone him. Instead, he chose when to give it. [John 10:18])

In motherhood, I have found perhaps too much solace in Simeon’s words to Mary in Luke: “And a sword will pierce your own soul, too” [Luke 2:35]).

So the mother of the perfect child knew grief as a parent. She would experience deaths–piercings (not the fun kind)–of her own.

Because what is parenthood if not a series of events both piercing us and making us more whole?

Isn’t that what love is? As Miller reminds, isn’t death, followed by resurrection, at love’s core here on earth?

Grief as a Parent: Lean into the Sadness

I’ve been slowly moving through Dan Allender and Cathy Loerzel’s Redeeming Heartache, which reminded me that God longs to engage with us in the holy place of our sadness and pain. (You might like the post, Cry: The Hidden Art of Christian Grieving.)

We might suspect God wants us to leave our pain outside, thank you, during worship. But the Psalmists turn toward God in their loss and the kind of crying that lasts day and night (Psalm 42:3).

(Am I hearing some version of John Legend? Even when you’re crying you’re beautiful, too…)

Even the kind of suffering that asks where God is, and why he’s not acting (Psalm 88:14)

Name It and Claim it

I mentioned recently that I’m helping write a resource for those who help resettled families and refugees. In it, we lead refugees through an activity we call “Backpack of Losses.”

The facilitator loads a backpack with rocks scrawled with permanent markers of losses these people have felt: JOB. FAMILY. SAFETY.

A volunteer walks around the room with the backpack. They can remove the rocks by naming what’s written on each.

They can only cease to carry around the losses when they’ve named them, mourned for them.

Some blank rocks are left in the backpack—because grief is one of those things we realize more of as time goes on. My friend who lost her dad will feel his loss more when she wants to tell someone she’s engaged, or holds her first child.

What parenting losses would you name of yours right now, seemingly insignificant or catastrophic?

Rather than survival mode, we long for more than survival. We can do better.

I can lean into God with my grief as a parent.

Thriving can start to happen only after we acknowledge the griefs of parenting—when we embrace not a false narrative, but the whole enchilada: The crosses, the empty tombs.

4 Comments

Laura Way - 3 years ago

This is beautiful, Janel. You have a lot going on right now! I’m thankful that it seems like Holy Spirit is being a good Shepherd to your heart along the way. Miss you ❤️

Janel - 3 years ago

Miss you back! I know you get all this. So grateful for God caring for me, even when times feel thin. xo

Janel - 3 years ago

It warmed my heart to hear from you, Laura!

"Everyone thinks I'm okay" - THE AWKWARD MOM - 3 years ago

[…] Name your losses. […]